1. Cultural sites Online Visibility

Online visibility of a a cultural site can be considered a strong indicator of the institutional ability to activate the cultural heritage.

Hand in hand with the spread of the Internet and its penetration into everyday social practices of millions of people, the search for contents relating to a travel destination or a specific monument, has gradually shifted in terms of strategic influence from traditional channels – such as print media, television broadcasts, word of mouth – to online information resources (websites, blogs, forums, social networks). This holds particularly true for Culture and Tourism search, generally conducted by people with medium-high education levels and some experience in the use of Internet.

The spread of smartphones and the increased connectivity accelerate such trends, so that an ever growing number of people plan their trips via websites or mobile applications.

A study on The Impact of Online Content on the European Tourism [1] highlighted a positive correlation between the presence on the internet, resulting in greater availability of data and information accessible online and the ability to some destinations to attract increasing flows of visitors:

Destinations that make greater use of the internet in reaching customers have performed better than their peers in recent years. These destinations have gained market share from competitors, even after accounting for some other factors. Developed markets which have seen the largest gains in market share all have relatively high internet penetration, making good use of online channels to reach customers. Theory […] suggests that this is largely due to improved information flow supporting the market. Greece, Italy and Spain all have low internet penetration and only Italy has experienced any notable gains in market share over recent years (Oxford Economics 2013, p. 17).

The production of quality online contents, especially if translated into several languages, is an important (not the only one though) tool to promote and internationalize not only nations and cities on the whole but also specific monuments, museums and cultural sites in general. In countries with a stronger demand of cultural products and services (I.e the North European ones) people access regularly to museums web sites or online libraries to improve their knowledge or find information. [2]

For small cities and/or lesser-known or new museums and new monuments, digital innovation can be a key to increasing the number of its users because internet makes it possible to connect them with a potentially much wider audience:

What is clearer is that smaller destinations and attractions have more to gain from increased online exposure by being able to reach a wider audience. For example, the relatively smaller Saatchi Gallery in London and New York’s MOMA have both generated greater interest online than some of the larger museums in those cities (ibid, p. 33).

In addition, affordability, speed and ease of communication on social networking platforms raise user expectations about the way they can interact with (cultural) institutions. Consequently, the online presence and social activities have a positive effect on the possibility that visitors go to a place, photograph, share and recommend it raising other people interest and curiosity to visit that place.

Among the consequences of these developments, we notice that the the public opinion on the quality of a piece of heritage or cultural event depends less and less from the assessment of traditional agencies (institutions, critics, experts etc.) and it is instead increasingly dependent on user reviews and rankings based on social network sharing activities.

A paradigmatic example is that of the Domus Romana di Palazzo Valentini, ranked second on Tripadvisor among the attractions in Rome that visitors consider an excellent experience (source: tripadvisor). In this case, the archaeological site, in spite of being interesting, is anyway inferior to other monuments (eg. Fori Romani), but the experience, supported by the use of lights, video and digital installations is greatly appreciated [3].

Similarly, in June 2015, the Casa Museo Stanze al Genio in Palermo, run by a small local association which houses a private exhibition of ceramics – ranked second on Tripadvisor behind the Church Santa Maria dell’Ammiraglio (La Martorana) and ahead of other very significant places such as the Church of Santa Maria del Gesu, the Palatine Chapel etc.

It is difficult to measure the impact of such rankings, generated by online social interactions, in terms of sales and tickets but the digital exposure helps to increase in a viral way visibility and level of interest of potential users and visitors.

Up to now Italian cultural institutions have traditionally interpreted their mission as organizations pretty much devoted to protection and preservation of cultural heritage. Many museums and cultural centres lag still behind on technological innovation and their online activities are almost non-existent. A report issued by ISTAT shows a widespread backwardness of the museum system in this field: just over half of 4588 sites surveyed in 2011 have a website, less are those which publish an online events calendar and only few of them give online access to selected items (16,3% ) or has an online catalogue (13,3%) [4].

The scenario in Palermo, from which we started our research activities, does not differ much from the national one. Most of the museums and historic monuments do not have a dedicated website and few sites display a foreign language version. Even the City of Palermo official webpages about the tourist information are published only in Italian.

Activities on popular social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram are also weak. Only in few cases such activities reflect a systematic commitment to interact with the public of a cultural site. Local cultural institutions attitudes toward online communication show a lack of awareness about the strategic dimensions of a constant presence online.

The most important museum sites of the city are fairly absent on online social networks, especially on Twitter, the platform on which less than 10 sites have an official account.

At the beginning of March 2016 The Fondazione Teatro Massimo was among the most active online civic institutions. The Massimo Opera House boasts the most followed and dynamic accounts on the main social network platforms, close to the average performance of the most active Italian cultural institutions, over 25,000 likes on facebook page and over 5,000 followers on twitter. The Teatro Massimo is also the only institution with a presence on other social platforms, being active on Instagram, with nearly 3000 fans, on youtube and google plus. Although it is not possible to evaluate the impact in terms of sales of theatre tickets and guided tours thanks to this communication effort on several fronts, it can still be assumed that the great online visibility of the Teatro Massimo will help to consolidate its role as a reference cultural site to Palermo.

In the following paragraphs we will see how such an increasing exposure can contribute to internationalize the city of Palermo positioning the Theatre as an urban “attractor” of international flows, a new landmark alongside traditional monuments of the city tourist landscape (Cappella Palatina, Church of San Giovanni degli Eremiti etc.).

In second place, the official page of the Cantieri Culturali alla Zisa (a huge brownfield area, partially restored and used for cultural purposes) on Facebook, which boasts about 14,000 like, although the latest content published – at the time of our survey – dates back to the end of 2014. To third place on Facebook for fans, the Modern Art Gallery official page GAM (11.000), more active than other local institutions, even on Twitter (2,500 follower). Interesting is the case of the Salinas Museum, very active online in spite of being still virtually closed because of restoration works [5].

2. Online Presence and heritage internationalization

The quantitative data we have briefly considered show a low level of attention by many local institutions towards the potential advantages of online exposure for a cultural institution or tourist destination. Besides, the content published by most of the websites mapped during our research activities, shows a substantial misunderstanding of the nature and characteristics of online communication flows and thus why it is useful to develop coherent and broader strategies in this field.

Generally speaking, the attitude towards the online presence as they are revealed by the reading of websites and social network pages of the main cultural institutions in Palermo (with very few exceptions) oscillates between two extremes.

On the one hand we observe a mere transposition of contents and information designed for offline use into online channels. On the opposite side there is instead an almost fetishistic trust in the miraculous virtues of the web marketing tools such as an ongoing conversation with users and its new ‘priests’, embodied in the figure – more and more widespread – of the social media manager.

In the perspective of heritage internationalization, digital innovation processes are important to overcome the opposition between a reductionist attitude according to which, to paraphrase Clausewitz, online contents are merely the continuation of the offline flows by other means and another one according to which, to paraphrase Sraffa, online communication would be immediately utilizable and therefore useful in an e-marketing approach aiming to produce conversation flows by means of conversation flows.

Common to both of these perspectives is that communication flows are seen as a ‘prosthetic device’ and the cultural heritage as a physical support on which the digital communication is applied just as a prosthesis.

In contrast, in the perspective of digital innovation, such as the one that we intend to propose in this paper, the knowledge of the potential of technological tools and the use of online platforms for content distribution can help to guide the process of internationalization of the assets provided one can capitalize on the wealth of information that can be drawn from the contents published and shared online by users (residents, tourists etc).

Unconventional analysis of such contents, that is analysis of the immaterial flows of information uploaded online, can relevantly contribute to the study of social practices, appropriation and re-signification processes of the cultural heritage sites by local and non-local users, permanent or temporary residents, tourists and so on.

Such Data may contain geographical and spatial reference elements that help to map and geolocate on territory “life fragments” of social media platforms eg. Instagram and Twitter) users. In this way researchers can widen the range of available information since traditional knowledge channels (eg. census data) lag behind the need for access to updated data.

To illustrate the potential of this approach we present here a preliminary investigation on the wealth of online information flows and their potential applications, based on a data collection campaign from the Instagram and Twitter platforms [6] .

3.Palermo is a flow: exploratory survey on Instagram and Twitter

The choice of monitoring streams of two different social media platforms is due to the fact that Instagram and Twitter have different characteristics not only in terms of “specialization”, i.e. of the type of information returned, but also in terms of database structure and stream data mining procedures and approaches.

3.1 Twitter

Tweets provide direct and indirect indications on the geographical space as a function of their geolocation (eg. “I’m going to work”, “I’m at work”, etc.) providing a kind of lifelog of the generic user [7]. Tweet data contain a wealth of information, including some particularly interesting elements such as Time which indicates when a Tweet was posted on the web by a user; Space which identifies the location (latitude and longitude) where the user was at a given time; Status which describes a particular state (as text) that the user shares with the web. Such information is often the most complex to decipher due to the countless tag that may contain, but at the same time it is also the most potentially rich in information to be encoded. It should be noted that, as regards the temporal data analysis, the Twitter information can be collected and stored only in real-time mode, or through a direct and not deferred streaming, so that the research design has to be accurately planned in advance.

3.2 Instagram

Instagram is a social network based on images and short video sharing. Instagram strength lies in the ability to “geotag” the user and the image to a certain physical place and at a particular time. Instagram semantics is based on the data extractable from the picture and on the concept of hashtag, that is a label used as a thematic aggregator. Hashtags are created by adding the ‘#’ symbol as a prefix to a single word or a phrase that consists of concatenated words without whites. They can be virtually affixed to the depiction. Instagram data contain a wealth of information and parameters, including Time which indicates when a photo was published on the web by a user; Space which identifies the location (latitude and longitude) where the user was at a given time; Tags which contains the list of user-chosen hashtags to describe the pictures and associate it to people, places, situations etc.

The data collection campaign was launched on an experimental basis in the month of April 2015 and ended in May of the same year. As for Twitter, the data collected at the end of the monitoring period amounted to more than 20,000 geolocated tweets throughout the country.

As for Instagram 150 geotagged photos (which means that users added a location to their pics) were collected with the following hashtag: #teatromassimo, #vucciria, #ballarò, #castellozisa, #duomomonreale, #cattedralepalermo.

Hashtags have been chosen after a test period so as to intercept some more places represented and therefore potentially more present in the collective imaginary of digital goers, residents, tourists, temporary city-users.

Furthermore, as regards Instagram, we also collected data on European scale with a wider time window, to intercept, with backward trend (from May 2015 to the end of 2013) some hashtags deemed useful for a benchmark analysis to compare some cultural/urban sites of Palermo and International landmarks of the same type (i.e the Cappella Palatina in Palermo and Aachen).

Here we present and shortly discuss the results of our analysis on three opera houses: the Teatro Massimo in Palermo, the Teatro alla Scala in Milan and the Teatro San Carlo in Naples.

4. Scope and first results of a preliminary study on social media platforms

As we mentioned above, the assumptions underlying the data collection on social media platforms is that the study of contents shared online by users of a city or a cultural institution, can provide useful information to map mobility flows, city users trajectories and social practices [8]. On the basis of these indications we can analyze the local and non-local relevance of some areas or sites in a city, identifying drivers and pivot able to boost and lead a process of urban internationalization. Among other advantages, such analysis makes possible to map collective imaginary and social trends in real or almost real time, paving the way to understanding trends while they are actually happening, something which is not always possible with traditional social research tools.

4.1 Mobility and trajectories on twitter

As it regards mobility flows and trajectories through the city we looked at the activity of two different types of travelers, classified on the basis of their Twitter activities once arrived in Palermo: the Cruise ship tourists who starts its visit to the city from the harbour and the traveler landing to Palermo airport.

In spite of the short span of time considered, it was possible to isolate few profiles and identify real trajectories shared online by individuals. Once stored in a database, Twitter data have been filtered considering cruise ships arrivals scheduled in the period between April and May 2015 and the users who logged in at the Falcone and Borsellino airport and who, according to the twitter archive, are not frequent users of the city. The outcome of this data mining activity is represented graphically in the map no. 1 which shows the routes and the stops of the city’s visitor and the places in which it has been tagged (eg. “I’m at Teatro Massimo”). The map does not represent statistical movements but actual movements of people who posted tweets to share their experience of the city, during their stay in Palermo. Through the collection and analysis of tweets we can therefore access a sort of ‘detection’ of places that city users judged as relevant and share-worthy. As showed in the map out of 5 itineraries two represent cruise ship tourist movements and three visitors arriving from the airport.

The analysis of mapped journeys highlights five different ways of using and crossing the city from which they emerge already, despite the small number of people we ‘followed’, some common elements along with some understandable differences.

The analysis of mapped journeys highlights five different ways of using and crossing the city from which they emerge already, despite the small number of people we ‘followed’, some common elements along with some understandable differences.

In particular, what we can notice on the map is a first trace of the symbolic weight of the Teatro Massimo, which is marked by a tweet in three journeys out of five. In general, as its social media exposure shows, the Teatro Massimo can aspire to the role of new urban Landmark of Palermo. In fact, as we will see from the Instagram data analysis the Opera House is already one of the most recognized symbols of the Sicilian capital.

Historical food markets (Il Capo, La Vucciria) and the Palatine Chapel are among the places seen and mapped by the cruise ship tourists, while Monreale (a Municipality few miles from the Palermo City Centre) is for logistical reasons more easily reached by travellers coming from the airport and with more time than the few hours visit allowed by the Cruise ship stop.

4.2 Instagram

The analysis of information flows on Instagram has been very useful to monitor the “weight” and to measure the international attractiveness of some sites and monuments (and hashtags associated with them).

We applied this method to some places, traditionally present in the local and international imaginary of the city such as the traditional food markets, the Teatro Massimo Opera House and few Arab-Norman sites (Palatine Chapel, the Cathedrals of Monreale and Cefalù) recently (July 2015) included in the UNESCO World Heritage List.

The results of the analysis conducted on instagram posts proved to be particularly significant when we took into account the information flows related to the Massimo Theatre.

The case has been chosen for the particular history of the Theatre as a Cultural site. Closed to public for works and almost invisible behind a fence for decades, the Palermo Opera House literally re-emerged in the cityscape only in 1997. After being re-opened the Theatre has gradually recovered its visibility and during the last two years has seen an increasing attention by tourists.

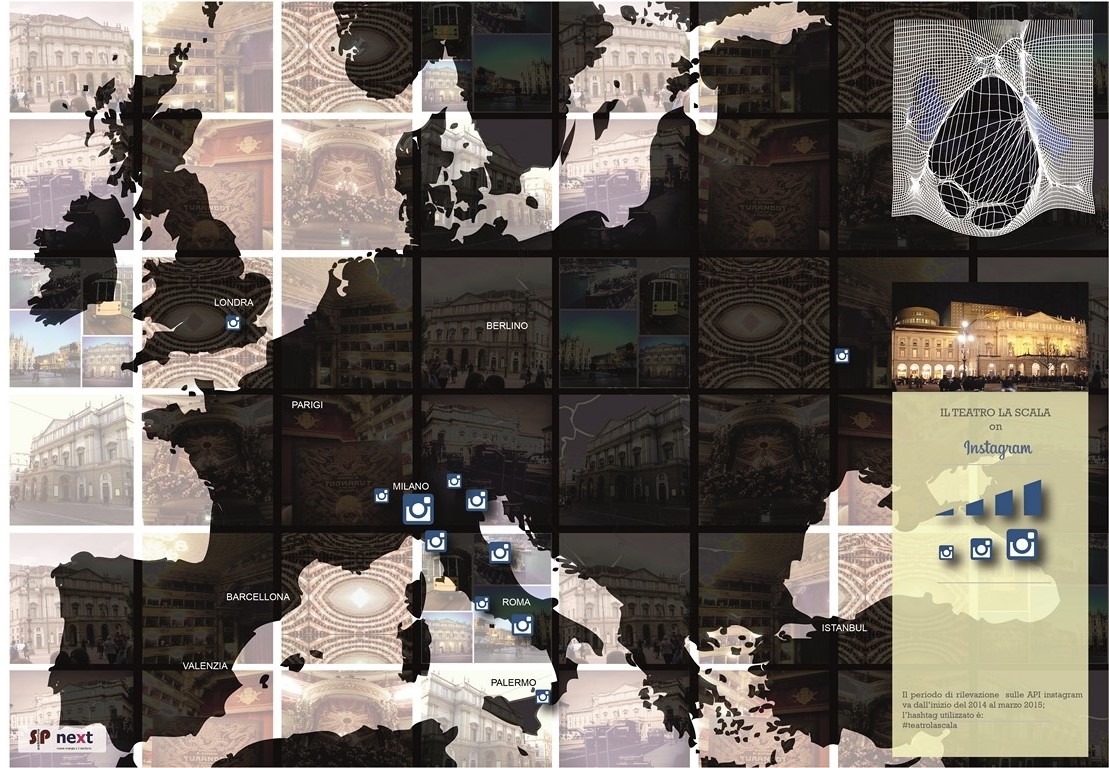

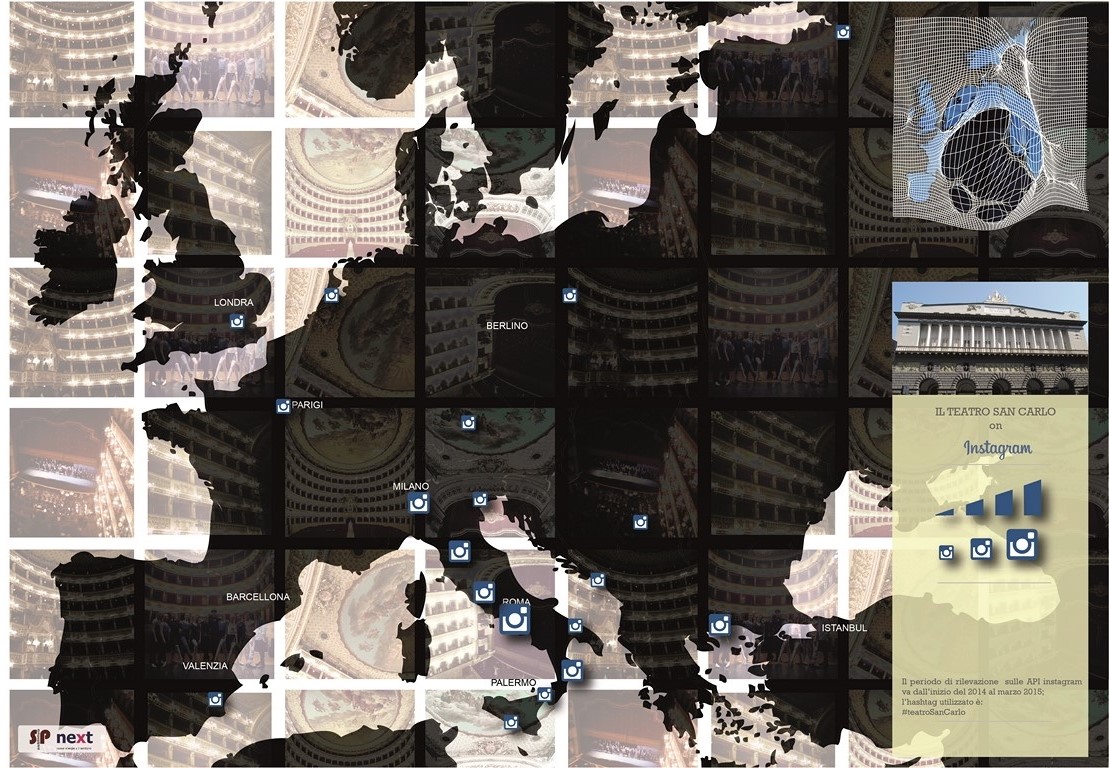

The map no. 2 shows the number and the spatial distribution in Europe of Instagram citations of the Teatro Massimo.

The survey covers the period January 2014 – March 2015 and focuses on the hashtag #teatromassimo. The Instagram icon shows that in a given location images have been shared. The size of the icons is proportional to the number of photo citations, posted with a specific hashtag.

Palermo – as expected – is the city which shows more shared images. We can assume that the majority of photos have been shared online once shot. But there is a good distribution in the rest of Italy, with peaks in Rome and Milan (city from where many visitors come to Palermo). Even more significant it is the presence of images of the Theatre, posted in several European cities. The international distribution of posts is coherent with the provenance of the main non-Italian tourist flows towards Palermo (Germany, France, Spain, UK) but it shows a significant activity also in Eastern Europe and Turkey, suggesting a further analysis of the Theatre Massimo attractiveness on residents in those geographical areas. A look at the subject of the posted photographs also shows the prevalence of images of the Theatre exteriors and especially the front of the theatre.

Such results confirm the hypothesis that the Theatre – thanks to its monumental size and probably also thanks to the recent proactivity shown by the Foundation Teatro Massimo on social networks – constitutes one of the new urban landmarks, that is one of the landmarks on which the self- and external image of the city as a whole is being built during the last years.

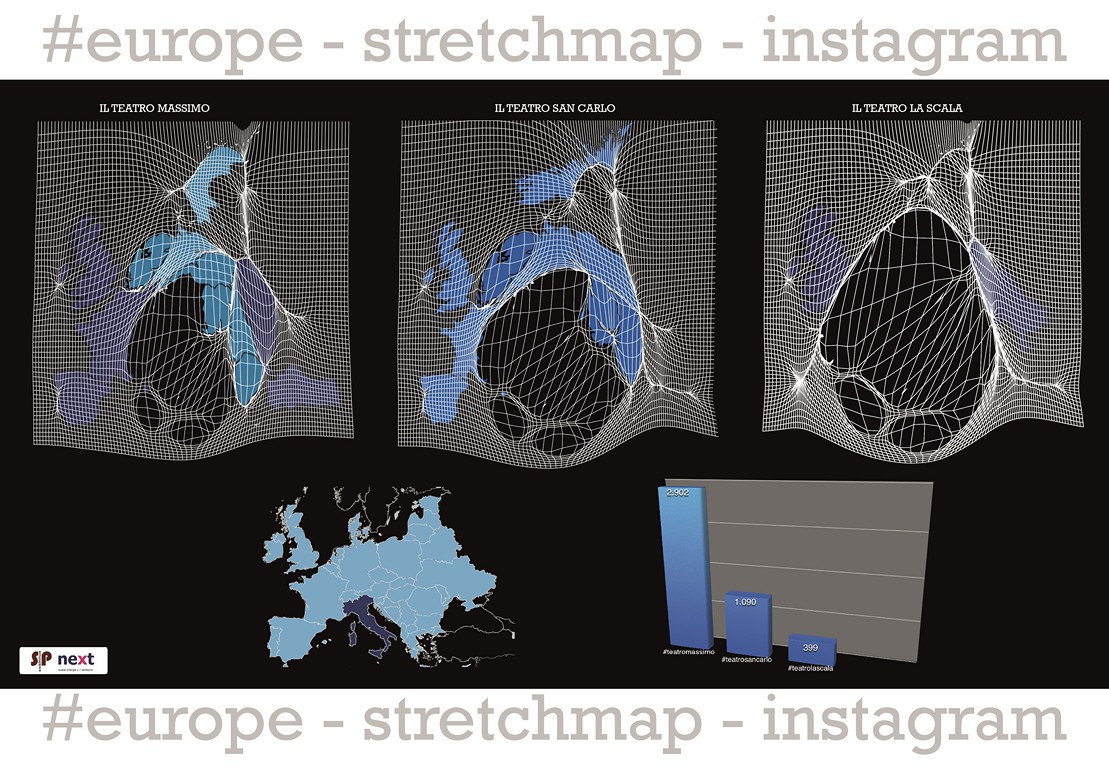

The role of the Teatro Massimo as a new landmark is confirmed both by comparative analysis at the local level and at non-local scale. To evaluate the level of internationalization of the Teatro Massimo as a symbol of the City, we compared the Palermo Theatre and two other national opera houses, il Teatro alla Scala in Milan (map no. 3 ) and the San Carlo in Naples (map no. 4), using the hashtags #teatrolascala, #teatrosancarlo. Comparing the maps on a European scale resonance of the three Theatres, the Teatro Massimo of Palermo boasts an higher overall distribution of Instagram quotes at European scale than the other two opera houses. The Teatro Massimo is the subject of a greater number of posts than La Scala or the San Carlo Theatres which also have a higher concentration of shares in the Italy than in the rest of Europe.

To this we can add the specific differences in the subjects represented by the photos (see the background of the maps 1-2-3). As for the Teatro Massimo there is a prevalence of photos of the outside, in the other two cases, the majority of photos posted relates to the interiors and the decorative details of the rooms. Not surprisingly, considering that La Scala and the San Carlo have been considered by National Geographic, respectively the first and second among the ten most beautiful theatres in the world (Top 10 Opera Houses 2015). La Scala also is undoubtedly a world landmark for fans of Opera and Ballet, but the building itself has no architectural features to also play the role of urban symbol of Milan to an extent comparable to the Teatro Massimo of Palermo (or in Milan to the Duomo itself).

The next cartography (map no. 5) shows, through a deformation effect, the degree of internationalization – within the Instagram environment – of each of the three theatres: the greater the number of Instagram citations in a given European nation, the greater will be the degree of deformation of the area concerned. In particular, to a greater level of Italy’s expansion we can record a lower level of internationalization on a European scale, while a less deformed Europe returns a more homogeneous distribution of Instagram citations, or a higher level of internationalization of the architectural good. In the case of the theatre of Palermo, it is evident that Europe as a whole is less distorted and the specific countries more visible; in the case of the San Carlo and even more in the case of the Opera of Milan, Italy appears much more inflated, producing a ‘disappearance effect’ of the other European countries. Hence the hypothesis that the city can focus in the future not only on the Unesco itinerary but also on the Teatro Massimo as one of the main symbols of Palermo and internationally recognizable urban landmark.

The last graph (map no. 6) underlines that the investigations on the Instagram data stream allow approaches not only at European scale but also at smaller urban scale, so that we can change the scale of observation as if we had a sort of ‘urban microscope’. This opportunity makes possible to observe social phenomena in the urban context with a higher level of detail, also positional. Therefore, looking at the historical center of Palermo zooming from the European level, we can easily recognize reverberation effects of the landmark considered. Interestingly, the same map not only strengthens the hypotesis on the role of the Teatro Massimo as a new landmark of Palermo, but the we can also track attractors significant at local level as the area of the Zisa, where the brownfield site Cantieri Culturali alla Zisa hosts cultural institutions and educational activities, produce a spatially recognizable glare on social networks.

Conclusions

Streams of public data flowing and extractable from social media platforms have an informative potential still not entirely coded, which requires further inquiry and research to deepen understanding and pilot projects to test applications and informational content. However, it is already clear that analysis of contents shared on social media platforms by users of a city or a cultural site offer significant information to map social practices and city users flows. Standing on these data, we can read the local and non-local relevance of cultural institutions and sites in a city, identify drivers and pivots [9] able to boost and lead a process of cultural innovation and urban internationalization. Digital Research based on the method we shortly presented in this paper makes possible to reconstruct social trends and communities thanks to a real or almost real time ethnographic tool box [10].

An increased knowledge on the relationship between users of a city and its tangible and intangible cultural heritage can have a positive impact on the ability of local institutions to redesign their contents online, to building or consciously repositioning the role of specific sites or cultural institutions within the strategies of urban attraction and internationalization. In this perspective – which suggests a reversion of the usual direction of the attention paid to social media by museums and cultural institutions – the social media platforms have much more to offer to cultural and city managers than an arena for emarketer and social media experts to upload storytelling pieces. The incredible amount of data shared everyday by all of us, when we cross cities and share our tourist and cultural experiences, come before web marketing. Therefore they can be considered as a valuable and not easily replaceable source of research and knowledge to better understand the current and future public of museums, cities visitors and culture users.

Quotes

[1] Oxford Economics (2013), Impact of Online Content on European Tourism, November 2013 (http://www.oxfordeconomics.com/my-oxford/projects/246666)

[2] Special Eurobarometer 399, Cultural Access And Participation, Report 2013 http://ec.europa.eu/COMMFrontOffice/PublicOpinion/index.cfm/ResultDoc/download/DocumentKy/57359

[3] Federculture – Formez, Cultura & turismo locomotiva del paese, Report Febbraio 2014, p. 23.

[4] Istat (2013), I musei, le aree archeologiche e i monumenti in Italia, http://www.istat.it/it/files/2013/11/Musei2011-28nov.pdf?title=Musei+e+monumenti+in+Italia+-+28%2Fnov%2F2013+-+Testo+integrale.pdf . See also Francesca De Gottardo e Valeria Gasparotti (2014), American Museums versus Italian Museums online: are they so dissimilar?, TAFTERJOURNAL N. 76 – OTTOBRE (https://www.tafterjournal.it/2014/10/06/american-museums-versus-italian-museums-online-are-they-so-dissimilar/)

[5] Bonacini (2015) “Open by vocation”: The Museum Salinas 2.0 and the sicilian anomaly in a social key, TAFTERJOURNAL N. 85 – Novembre – Dicembre https://www.tafterjournal.it/2015/11/15/open-by-v

ocation-the-museum-salinas-2-0-and-the-sicilian-anomaly-in-a-social-key/

[6] The preliminary study we present has been conducted by Manifattura Ricerche Digitali a spin off of Next – Nuove Energie x il Territorio and S&P Architettura (http://www.manifatturaricerchedigitali.it/). See also for a comparable approach Agata Ludzis-Todorov – Ludmila Girardi (2015), Making Sense of Big Data – Presentation of the “Marseille speaks, in & out, on Twitter” Project, E-methodology International Scientific Journal n. 2.

[7] See Kalev Leetaru, Shaowen Wang, Guofeng Cao, Anand Padmanabhan, Eric Shook (2013), Mapping the global Twitter heartbeat: The geography of Twitter, http://firstmonday.org/article/view/4366/3654#author

[8] (2014) Katrin Weller, Axel Bruns, Jean Burgess, Merja Mahrt, & Cornelius Puschmann edd., Twitter and Society, Peter Lang Publishing, Inc., New York

[9] See Giambalvo – Lucido (2015), Gli artefatti della storia nei processi di internazionalizzazione di Palermo, Fondazione Sicilia.

[10] Caliandro, A. (2014). Ethnography in Digital Spaces: Ethnography of Virtual Worlds, Netnography, and Digital Ethnography, Handbook of Anthropology in Business, ed. P. Sunderland, and R. Denny, Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.